Year XXXIX, 1997, Number 1, Page 9

A Macro-economic Setting Favourable to Employment?*

JACQUES DEFAY

The current macro-economic setting of the European Union is not favourable to employment. Our young people who finish their studies have the distress of not finding work. Their fathers or mothers have been victims of a company restructuring, or fear they will be any day. Already the time is almost forgotten when their grandparents prepared for retirement at the legal age (and not ten or twelve years too early), and did so serene in the expectation of a comfortable, secure old age. The harsh reality is that the post-Maastricht European macro-economy is not a very welcoming environment for young workers, not very encouraging for young entrepreneurs, and not very reassuring with regard to the great mass of citizens worried about their own old age.

There is general uneasiness among workers. When discussing Europe with them, one soon notices that they are not very sure whether to blame “too much Europe” or “not enough Europe”, nor indeed how they might make this choice. That puts them in bit of an awkward position, because the choice between “too much” or “not enough” has been raised and will be raised again in referendums. “It would be nice to know on which side our interests lie”, they say.

If one tries to explain that the Treaty of Maastricht is off balance on the social level, and that everything will be better once the IGC has restored the balance by creating an “employment committee” as powerful as the “monetary committee”, they look bemused because they have not the slightest idea of how European decisions are taken. Then one has to explain that the IGC means the “intergovernmental conference” and that in it the fifteen governments have the power to reform the Treaty of Maastricht but that they only take decisions unanimously. The majority of ordinary citizens cheerfully confuse the Commission with the Council, are unaware that the European Parliament exists, and are also unaware that there is a European Court of Justice before which European laws, called “directives”, rank above national laws, which must moreover be brought into line with the directives. They do not know in which domains the European machine is competent, nor those where it has nothing to say. They also confuse the beginnings of competence with a plenitude of power, a mistake which allows them to blame the “bureaucrats in Brussels” for unemployment and other social evils, in particular insecurity, but also the whittling away of social protection. They even wonder whether the “single currency” will not ultimately attack their retirement pension. “It’s not certain, but you never know! After all, will securities denominated in the national currency still be worth anything when the euro is the single currency?” This is what one hears.

They have also vaguely heard talk of a “great enlargement” which will bring into the common market ten ex-communist countries totalling a hundred million inhabitants. They say: “That will cost billions! Where will they get the money, if they don’t get it from our pockets? Besides, the Poles, the Romanians, and the others earn next to nothing. Once they are in the ‘common market’, hundreds of factories will relocate. It will be even worse than globalization”.

Thus, since 1992 Europe as an institution has been losing the hearts of ordinary people who understand nothing about it and who see in everyday life what the statistics record: that Europe as a society is sick, suffering from unemployment and a lack of future, and that for these two evils it has been unable to find a cure in the unification of its internal market. This reputedly ineffectual Europe has become the target of many criticisms, and the referendums due to ratify the text that will emerge from the IGC will be lost, we are told. As with the referendums of 1992 therefore, what is written in this text is of little importance. Unemployment, anxiety and the absence of hope are reason enough to say “no”.

The real danger is not the failure of the IGC. A more serious matter is failure to ratify in one country alone, for a year will be lost in seeking a sordid compromise, just as 1993 was lost. Failure in five or six countries would be even more serious, for it would throw discredit on the construction of Europe. After the elections in the new member-countries, let us not rush blindly in. Let us for a while drop the search for obscure compromises worked out in the faint hope of achieving unanimity, and listen to the citizens.

For more than twelve years I have been a resolute partisan of the single currency and I am inclined, by heart and by reason, to support M. De Silguy’s courageous optimism. I think it will be achieved in 1999 and that it will help the birth of a political Europe. However I have no illusions about the difficulty of awakening the European hope in hearts where it is still dormant, and of restoring confidence by this means at the time of referendums, which are set for dates when the macro-economy of Europe will still be what it is today, which is to say deplorable. This difficulty is immense.

Having seen that I was lacking a coherent set of arguments, I have tried to write one for my personal use. The point of departure of a political set of arguments is a socio-economic diagnosis.

The Diagnosis of Unemployment and Slow Growth.

The least questionable diagnosis has been made by the white paper “Growth, Competitiveness and Employment”. We suffer from slow growth which creates few jobs.

Let us trace this analysis of growth. It is slow. This has lasted since 1980.The average rate of growth in real terms (i.e. minus inflation) of the last fifteen years is 2 per cent. In the sixties it was 4.8 per cent. In the seventies it was still 3 per cent.

It creates few jobs. Employment has risen on average by 0.2 per cent annually, or ten times more slowly than production and twice as slowly as population. Too slowly therefore to provide work for the annual surplus of young people over newly retired people. Growth in production is barely sufficient to compensate for the effect of progress in productivity, which as everyone knows removes jobs if sales do not grow in line with productivity. Progress in productivity showed an average of 1.9 per cent during the eighties.

As a consequence of the influx of young people into the labour market and of growth which barely compensates for productivity, unemployment has gone from less than 6 per cent of the active population in 1980 to more than 11 per cent in 1994, with peaks of 25 per cent or more in regions undergoing reconversion difficulties or late development. This is intolerable.

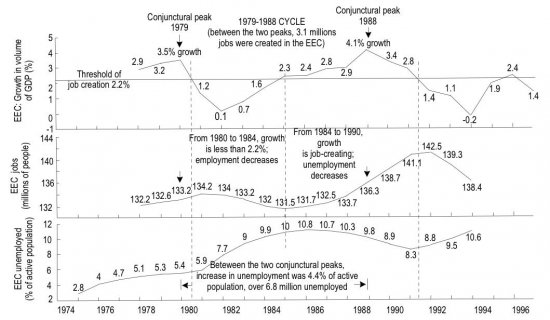

Moreover, growth has once more become strongly cyclical: the job destruction phase occupies almost half the trade cycle. The job creation phases are too short and not strong enough to bring down the accumulated unemployment, for they must first restore the jobs destroyed in the course of the immediately preceding phase. It is a real “Penelope’s web”. The damage done during the job destruction phase 1992-1995 is estimated at five million jobs lost (Graph 1).

The excessive amplitude of the sine wave of the GDP growth rate combines with the weak average of this curve (2 percent) in the following way: when a company’s sales figures begin to grow less quickly than its productivity, the company reduces the number of its workers. It will not begin taking on more until the year when the curve of sales exceeds that of productivity. As the national figures reflect the average situation of all companies, this threshold of job creation must be found in the phases of the trade cycle.

Indeed, through the sinusoid of the rate of growth one can trace a “productivity mark” at the level of about 2 per cent which indicates the moment at which the destruction of jobs ceases and the job creation phase begins. In the year 1996 we are at this transitional point of the cycle. Since January 1994 business has been growing. The rate of growth in sales (which had gone below zero) has taken two and a half years to overtake that of productivity. Penelope is therefore only now beginning to weave again the millions of jobs which she had undone during the dark years of the recession, between 1991 and 1994.

Four years of the creative cycle will be spent repairing this damage and very little time will then be left over, indeed no time at all, for the unemployment rate to drop below that of 1991. For the next phase of job destruction could begin around 2001.

Predictably enough, in lowering the average of the sine wave to the level of the productivity mark (2 per cent), we have divided the cycle into two almost equal phases: four years of destruction, four or five of job creation. It would be astonishing if that made workers and their families happy and confident.

What is required for unemployment to decrease? That the rate of growth in real GDP has to spend less time below the productivity mark and more time above it. That assumes a higher average for growth in GDP. Is this possible? Apparently, since the average of the sixties was 4.8 per cent, their minimum 3.4 per cent (in 1967), their maximum 6.1 per cent (in 1969). To bring the average from 2 per cent to 4 per cent therefore does not seem absurd. That, alas, leaves too many people incredulous. Can one not achieve the goal with a more modest objective?

In moderating our ambitions to an average of 3.5 per cent (instead of 4 per cent), the same goal could indeed be achieved by diminishing the amplitude of the cycle by a common conjunctural policy, so that at the bottom of the cycle there is not less than 2 per cent growth in real GDP, and not more than 5 per cent at the top of the cycle. In this hypothesis of a “smoother” growth, at an average of 3.5 per cent, the phase of net job destruction would be eliminated. The trade cycle would not have disappeared, but Penelope would have put her web away in the loft. The nine or ten years of the cycle would all be capable of adding jobs, some more and others less. The objective thus redefined will appear less inaccessible to our citizens, so demoralised by so many years of socio-economic ill-health that many have ceased to believe in recovery.

Observation: The Fifteen have not exceeded 3.5 per cent more than twice since 1980. They exceeded this figure 11 times during the thirteen years which preceded the year 1973, when the global monetary system was eliminated. First sign of a link between unemployment and monetary disorder. Does the reform of the currency therefore allow some hope of a different growth? My faith in the single currency makes me say, “Let’s try”. We shall soon see if one can rationally say “yes” to this question.

One word first of all to reassure the citizens, the majority of whom are more conscious today than yesterday of the dangers to the environment that can be caused by economic growth. It is true that the growth of the sixties was hardly respectful of it. Initially even a slogan like “zero growth” was launched. But at zero growth productivity continues to grow by around 1.6 per cent per annum. At a constant rate of work that would make 1.6 per cent fewer jobs per annum!

Fortunately zero growth is not the only response. There is another, involving changes in behaviour and the adoption of so-called soft technologies, and hence also substantial efforts in research and development. Today this growth is called lasting or sustainable development. I am not considering any other kind here. Equally one must remember that the progress of productivity is calculated over an entire year, and that it is slowed down therefore by working fewer hours per annum. The other growth, if it exists, will therefore take into account both the environment and the duration of work.

After the Diagnosis, the Clinical Recital of What Has Happened.

So what has happened? Has the European Community voluntarily diminished its growth rate? Has the grand unified internal market had this effect? The answer to both questions is no.

It is the governments of the member-states which have voluntarily reduced their national growth rates, and, by additive and even multiplier effect, dragged down that of the Union. This they did in the hope of conquering inflation, which threatened the national currencies. They chose this way at different times, some in 1980, others later.

The member-states of the EEC had decided in 1970 to switch to the single currency in 1980. This reform was to take place in the context of the world adjustable-peg exchange rate system, which had assured the stability of exchange rates since 1945. The world system had a major crash in 1971 and was eliminated in 1973, the year when the non-system of generalised flotation of paper money took root, which still holds sway.

In 1979, after six years of monetary turmoil and an inflation accelerated by successive oil crises, the Ten, like shipwrecked sailors among the fragments of their ship scattered on the raging sea, decided to assemble these planks into a raft to float together. From 1980 this raft, ambitiously called the “European Monetary System” (EMS), assured a certain stability in intra-European exchange rates.

The “system” left each country its currency and the responsibility for defending its pivotal rate, a difficult thing to achieve for countries where prices are rising more rapidly than the average. Thus it was the EMS that established disinflation for the defence of the national currency as the central objective of national economic policies.

Nevertheless, the will to conquer inflation is not entirely circumstantial. What economic history will call the “long inflation”, since it began in 1968 at a rate of only 3.3 per cent and ended in 1993 (at 3.5 per cent), towards 1980 went through peaks of 20 per cent in Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Greece. The phenomenon was worldwide and had been accelerating continuously until 1980, the critical year when the average rise in prices of the Fifteen reached 12.5 per cent per annum under the effect of the three “oil crises” of 1974, 1978 and 1980. The effect of inflation on growth in real GDP had been disastrous, since from an average of 4.8 per cent before the price disease, it had fallen to 2 per cent average at the time of the oil crises.

The price fever had come early to Germany, England and the Netherlands around 1970. It began to fall in 1981, first in Germany and the Netherlands then successively in the other countries as they converted to “disinflation”, but the thermometer was not put back in the drawer until 1994. Disinflation will thus have lasted fourteen years, during which national economic policy has been dominated by the all-important objective of restraining national global demand successively in Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, France, then in Italy, etc. The important thing was to reduce the price rise in the national currency so as to defend its pivotal exchange rate on the EMS raft. But the long years of disinflation 1981-1993 brought no improvement in growth since their score is still 2 per cent of annual average real growth, exactly the same average as during the years of strong inflation. One reading of events: inflation breaks down growth, and hence employment; disinflation heals prices, but not the macro-economy.

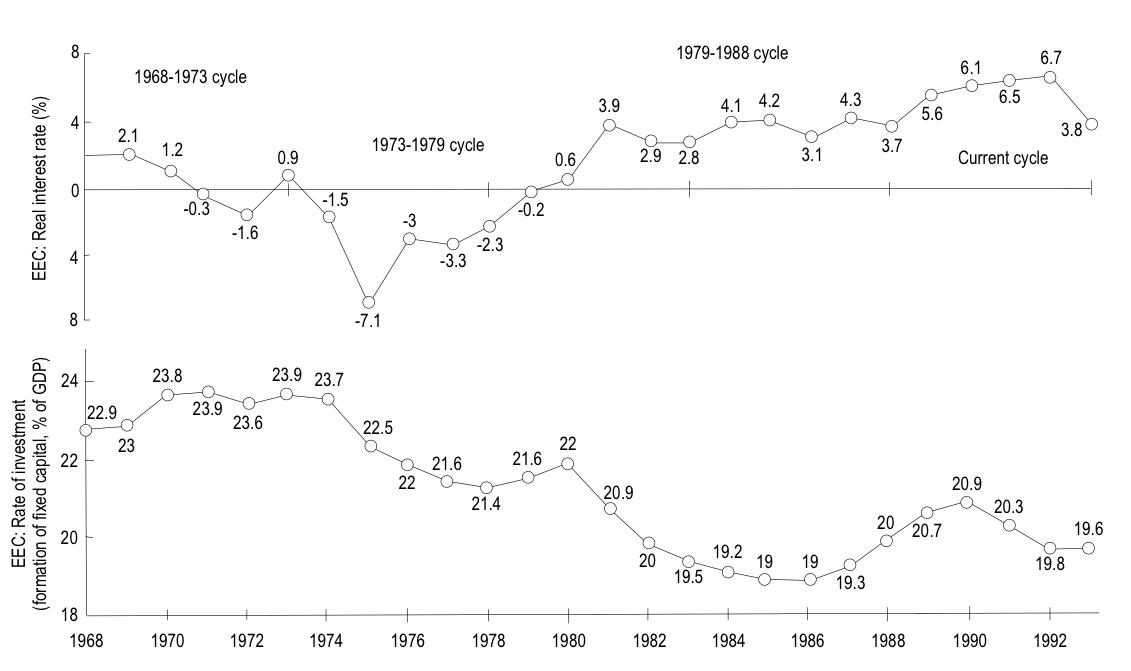

Obviously it could not be otherwise, since recovery was sought in a systematic diminution of demand, including a reduction in demand for investment goods, which was obtained by a deliberate rise in the real interest rate. Thus the average of real (short term) interest rates practised by the authorities of the Fifteen current member-states went from 1 per cent in 1980 to 6.3 per cent in 1990 and even 7.1 per cent in 1992, figures which must be compared with those of the past. The European average of real short rates was between 1 and 2 per cent in tempore non suspecto (1966-1968). A dose of more than 2 per cent of this elixir in this golden age would have been considered as a brake on economic performance (Graph 2).

If a sick person is finally healed of his cancer, he will not regret the chemotherapy. But it cannot be denied, for all that, that chemotherapy is toxic, nor that it has perceptibly weakened the vitality and energy of the patient during a long course of treatment.

The dose of real interest applied as a disinflationary cure was 5 times the dose of a healthy macro-economy and 2 to 3 times what one would have previously considered as a threshold of toxicity (around 2 per cent). The dose of this “remedy” (which I have just compared to chemotherapy owing to its toxicity), was even reinforced further and brought to three and a half times this threshold in 1992, in the third year of a severe recession and at the peak of its job destruction phase.

This latter syndrome, which led to the almost fatal crash of the EMS in 1993, was highly toxic because it was inflicted at the most painful moment of the trade cycle on a European economy already weakened by twelve years of disinflationary austerity. The investment rates (gross formation of fixed capital in per cent of GDP) of the Fifteen, from 24.3 per cent in 1970, fell in 1994 (Year I of Maastricht) to its historical minimum: 18.3 per cent. Now, this rate is the equivalent for an economy of the measure of energy for an individual. It is as if arterial tension had fallen from 12 to 9.

Back in 1993 Jacques Delors’ White Paper identified the drop in investment rates in Europe (5 points lost in 20 years) as one of the causes of unemployment growing from cycle to cycle. It also identified structural factors of unemployment in those national policies of taxation and compulsory social contributions which put a disproportionate share of the social burden onto wages, thus putting up labour costs to companies. But the structure of fiscal and fiscal-like revenue is a national prerogative protected from community intervention by the unanimity vote.

Let us recall from the clinical recital that the artificial stabilisation of the intra-European exchange rates decided in 1979 contained an automatic mechanism, resulting from the competition between eleven currencies, which made real interest rates rise and lowered investment rates. Even without the drive for disinflation, the interest rate would have been too dear. Perhaps a little less dear, all the same.

The Question of Responsibilities.

The European Community and Maastricht have no responsibility for the therapy chosen for disinflation.

This is not the time to put the national doctors on trial, since the patient has finally emerged from their hands cured. One cannot even put the chief doctor on trial, by which I mean the Bundesbank, even though it manifestly forced up the dose of chemotherapy at a time when the patient was already deteriorating fast. In associating themselves in 1991 with the single currency project (though with not entirely justified demands and with a tinge of scepticism), the directors of the Bundesbank recognized that the system cobbled together in 1979 to stabilize the exchange rates of ten or twelve competing national currencies was fragile, and that the unification of the internal market, effective since 1993, makes that of the currency imperative. The part they took in 1991 in this diagnosis and in the writing of the monetary chapter of the treaty of Maastricht (therefore before the 1979 system collapsed in 1992-93) means they cannot be compared to those doctors in Molière who kill their patients by useless blood-letting and excessive doses of purgatives.

Our task is to explain to the ordinary citizen, bruised by fifteen years of slow growth yielding few jobs, (i) that disinflation was necessary because the growth rate falls when the currency is sick, (ii) that the single currency is no less necessary because the other means of stabilizing intra-community exchange rates, the EMS model, is fragile and involves a rise in interest rates because of the competition between national currencies (behaviour which the jargon terms competitive disinflation); and (iii) to show him the national responsibilities for an unjust situation born in a period when the European institutions had no powers in the areas of the interest rate and employment policy. It is hardly simple to demonstrate, but it is necessary, for the wounded but rational citizen has to understand the wasting disease of Europe in 1993-99 and want its recovery after the ratification of an appropriate reform.

If it is true that the price disease is cured at the conclusion of a perhaps uselessly long and painful treatment, if it is true also that the chief doctor who imposed this treatment is also the author of the obstacles placed by the treaty in the path leading to the single currency, and particularly of the preliminary convergence requirements imposed on each country in the area of public finances, we have to convince the bruised and disappointed citizen to save his anger to fight the new requirements which certain national ministers want to impose now, and which go beyond what was accepted when the treaty was ratified.

It is vain in fact to struggle for a revision of “criteria” which have slipped into the status of a ratified treaty, or for a postponement of the Euro, which this same treaty forbids.

On the other hand there is an urgent need to fight the plan to forbid exceeding 3 per cent of public financing of investment by borrowing in the job destruction phase (cf. table in annex), since it will be necessary to raise the growth rate above the productivity mark (2 per cent) when it passes this mark on the descent towards 2001. If a “stability pact” forbids it, it cannot be done. The cycle will then again destroy millions of jobs for four years.

The Waigel plan liberates the borrowing power of the member states if the growth rate of real GDP has fallen to “minus 2 per cent”. But it is at “plus 2 per cent”, according to our analysis, that the anti-cyclical treatment has to begin by supplementing public investments (Cf. Table in annex). This immediate battle however is nothing but a skirmish before another fight, even more crucial to win, in 1997: a reform of the treaty to make effective a common employment policy based on the single currency “respecting the stability of prices” (according to a stipulation which must not be thrown back into question).

The Question of the Social Europe, Employment and Lasting Development.

We have to convince the ordinary citizen that his anger is useful and necessary in order for a genuine policy for employment and lasting development to be written into the treaty of Union in due course by the Intergovernmental Conference; not only so that it remains possible to save jobs in 2001-2004, but also so that other social and environmental measures cannot be blocked by veto. This reform will not come about without ordinary citizens and their justified anger, the way things are going.

The most difficult message to put across, because it has an institutional aspect, and is therefore apparently “remote from the people”, is that a struggle of crucial importance for employment is going on right now between two modes of legislative decision: (i) the intergovernmental mode, which by its nature involves the national right of veto; and (ii) the new community mode, without right of veto, which is to say “by the Council, ruling by qualified majority, on the proposal of the Commission, after the advice of the Economic and Social Committee and of the Employment Committee, in co-decision with the European Parliament”.

It is of prime importance to spread the fact (scarcely mentioned by the press and television), that two European players, whose importance lies in the hundreds of millions of citizens they represent, have declared in favour of the new community method, to be applied for all competences of a socioeconomic and monetary Union for employment and lasting development. One of these players is the European Parliament. It has issued an opinion to this effect by a very strong majority of representatives, directly elected by the citizens of the Union. The other player is the European Confederation of Trade Unions, which brings together the trade unions of waged workers. It expressed the same view when the IGC was convened. The conjunction of the claims of these two organizations, one elective and the other associative, representing hundreds of millions of people, is such as to give great legitimacy to the political campaign for the new community mode of decision-making when the citizens begin to mobilize for it. This legitimacy, from the number of citizens, carries a lot of weight.

To Abolish the National Veto: the Big Question.

The citizens must be told that the national veto still exists: in social matters among others, in the area of taxation and social contributions, as well as for the environment and for research and, obviously, for external and legal affairs. An essential part of the means for fighting unemployment can therefore be paralysed by a single government, under the current state of the institutions.

Political debate is beginning to concentrate around a simplifying concept: to be for or against the national veto. When the Single Act was negotiated, Margaret Thatcher abandoned the defence of the national veto for the 300 directives which were necessary for unification of the internal market and which were to accomplish deregulation and privatisation, reforms which she wanted to succeed. She had the national veto maintained for social directives and those concerning taxes or social charges, which she wanted to be able to block. It was at the same time as the role of the Parliament in European legislation was enlarged.

The national veto is a simple idea which appeals on first sight. One only rejects it when one has perceived its hidden face, which is called blackmail. When a decision is urgently required and is wanted by a large majority of member countries and citizens of the Union, the government which vetoes it takes this majority hostage. It can demand anything of its hostage as payment for its “yes”. Even preferential treatment in another case! It can even extort money! It has been done.

In legal language this is called blackmail. The veto is at the very least a source of delays and blockages. At worst, it introduces into the Union shameful political customs which are diametrically opposed to transparency and democracy.

Today when they call for the veto to be abolished in all areas necessary to a common policy for employment and lasting development, including the macro-economic balances which govern the creation of jobs (investments, remunerations, certain deductions and taxes, the length of the working day, social security), the Parliament and the European Confederation of Trade Unions are adopting a process parallel to what was done ten years ago for the single market. This time, it is for employment that reform is demanded.

The great strength of this process is that the abolition of the national veto on European decisions is necessary to realise a political objective. It is therefore not an end in itself, nor a federalist dream, but a means in a plan to reform society. Europe is not chosen for itself, but because the nations who make it up are too small, or too closely interlinked to reform at their own level.

Chain Reactions Against the Veto?

The German government is anxious to reinforce the authority of Europe in internal or legal affairs (the third pillar, or internal security) before the great enlargement. The idea that anyone of 27 governments could paralyse the Union is particularly intolerable because it is by no means impossible that one of the 27 countries might be governed temporarily by fascists or communists following an unfortunate election. Citizens attached to the rule of law which must continue to prevail in the Union will not accept the risk that the Union could be paralysed or held up to ridicule by those who have trampled on its values and laws in their own country and will have deprived it (by their veto) of its capacity to react against them. Yet that will be the result if the third pillar, where the veto is king, is not reformed before enlargement.

The French government is calling for a strengthening of the common foreign and security policy (CFSP, or second pillar). It is convinced that if we continue to have fifteen foreign policies, the American position will continue to carry us along with it automatically. This can be observed today, even when it is a case of a European country (Bosnia), or African countries (Zaire and Rwanda).

These differences of sensitivity obviously destroy any chance of governments opposing the veto in one pillar or part of a pillar arriving at a compromise amongst themselves.

But if abolition of the veto was accepted in view of the social objectives of a common employment and development policy, and constituted a general measure for all that concerns the Economic and Monetary Union, who can fail to see that the two other pillars could not remain subject to the intergovernmental mode for long? The two forces which, although not invited to the IGC, are proposing a general measure in the first pillar, take on a new interest for those who are fighting the same battle in other parts of the treaty.

If the debate on the abolition of the veto were to penetrate people’s consciousness in the fight for employment, everyone would see that Parliament and the ETUC are advancing together, and Paris and Bonn separately, on three parallel routes. Euclid said that parallel lines never meet, but he was not a statesman... In politics, they always meet.

Can the National Veto Survive in Articles N and 235?

John Major’s verbal gesticulations give urgent cause for concern. He recently swore to take revenge on the Court of Justice, which dared to not find in his favour in an interpretation of the treaty. He declares that he will oblige the fourteen other governments to modify the treaty, under his dictate, on the point at issue. What weapon will he use to make them bend? The national veto, of course, since article N does not allow the IGC to present its conclusions other than unanimously. He will therefore refuse the text it is to deliver if it does not contain his vengeance! Well, if he is still at 10 Downing Street, obviously...

He therefore provides us with powerful proof that we have to put an end to unanimity, even for modifications of fundamental European law. Good sense would suffice to force this conclusion in any association destined to count 27 members. All the more then must a union of sovereign states, obliged by its statutes to advance by stages “in the process creating an ever closer union of the peoples of Europe” (article A), which means it must revise its competences and powers at every stage (perhaps once or twice a decade in the youth of the institution), be able to transform itself in legal security, without the possibility of any blockage or blackmail preventing it.

It would be quite normal for these revisions to be, as in any association, the work of its internal organs (in our case the Commission, the Council and the Parliament), and that the ensuing text should be adopted by a majority duly reinforced for the occasion. Those who still consider it necessary for each member state to ratify the modifying act should say what they see as the consequences of anyone country refusing to ratify.

Will this country automatically secede? Or will there be a negotiated transition of limited duration? Will the seceding country have the right to part of the Union’s assets? Will it, on the contrary, have to pay an indemnity or a right of exit? All this will have to find an answer in the revision in progress at the IGC, or a Maastricht III, but in any case before the great enlargement.

Conclusion.

A prognosis. Mrs Margaret Thatcher, in conceding the abandonment of the veto for the single market, made it possible to carry out liberal reforms by qualified majority. If the same way was not open to macroeconomic measures for employment and lasting development, the construction of Europe would lose the support of the popular vote — in the 1998 referendums, the sole day of reckoning to be feared.

Statistical Annex.

The trough of the previous cycle had led to the net destruction of 143.1 -140.1 = 3.0 million jobs. The trough of the last one destroyed 149.5 -144.9 = 4.6 million. The social damage of the economic winter therefore increased by more than 50 per cent from one decade to the next, which indicates a marked deterioration in the macro-economic environment of Europe. One will notice also that the net destruction of jobs does not cease immediately the year that growth once more exceeds the productivity mark. That is plotted at the level of an average. Employment begins to recover a little later.

The table and the graphs which follow clarify the phenomenon described as a “Penelope’s web”. They show that reflationary public investment is justified to prevent the GDP growth rate from dropping below the productivity mark during the four years of its falling curve, which constitute the phase of net job destruction. The Union’s growth rate in this phase is simply exceptionally negative. The device of the planned stability pact is therefore inappropriate.

The last two cyclical phases of job destruction

1981-84 and 1991-94

|

year

|

Real GDP

Annual growth

|

Millions of jobs

(fifteen countries)

|

|

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

|

3.5

1.4

0.1

0.9

1.7

2.3

2.5

|

142.0

143.1

142.8

142.0

140.7

140.1

140.3

|

|

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

|

2.9

1.5

0.9

-0.7

2.6

3.0

|

149.3

149.5

148.5

145.6

144.9

146.2

|

Graph1: Growth of GDP, growth of employment, growth of unemployment (sources: OECD, EEC)

Graph 2: Real interest and investment (source: ECC)

Statistical observation: the two graphs were drawn when the grey pages of the Commission’s review “European Economy” still only added up the data of twelve countries, data which have since been slightly enlarged to cover fifteen countries and have served for the table. This source does not give the absolute number of jobs, but the annual variations in percent. To establish this short set of numbers of jobs, I took the absolute figure of 1992 from the OECD “Economic perspectives” no. 59, table 20 of the annex, and combined it with the annual variations from the official EU series, for fifteen countries. The graphs ought to be redrawn, but will change little.